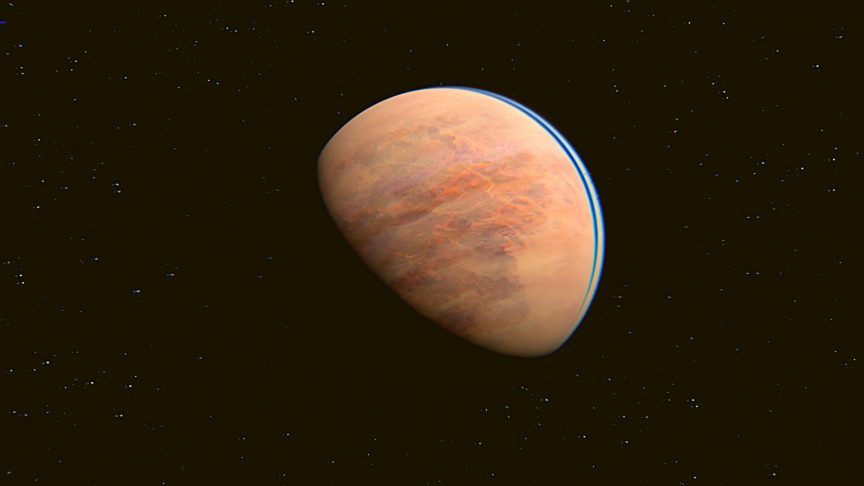

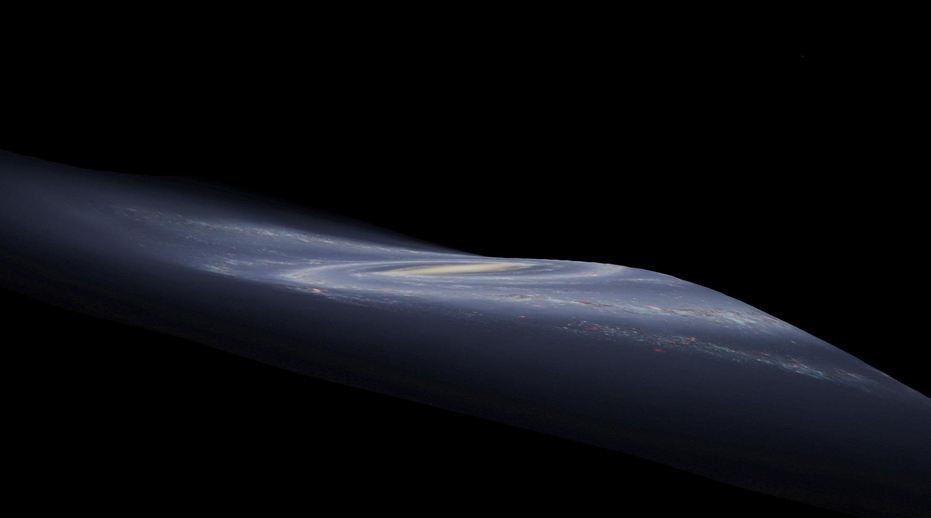

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has done it again, delivering jaw-dropping images that challenge what we thought we knew about how planets are born. This time, the telescope turned its gaze toward the Small Magellanic Cloud, a neighboring dwarf galaxy that, until now, wasn’t exactly considered prime real estate for planet formation. The star cluster NGC 346, nestled within this galaxy, has become the latest cosmic mystery unraveled.

A Discovery Decades in the Making

Back in the early 2000s, the Hubble Space Telescope made waves by spotting what appeared to be planet-forming disks around stars in NGC 346. These disks, rich with gas and dust, are like the cosmic kitchens where planets cook. But there was a catch—astronomers couldn’t confirm their findings because NGC 346 lacks the heavier elements, or “metals,” typically associated with planet formation. It was like spotting cookies baking in an oven without seeing any flour in the pantry.

Fast forward to 2024: the James Webb Telescope, armed with cutting-edge infrared imaging, zoomed in and settled the debate. Not only are these planet-forming disks real, but they also stick around far longer than earlier models predicted. “It’s a paradigm shift,” says Olivia C. Jones of the UK Astronomy Technology Centre. “We’re learning that planets might form under conditions we previously thought were impossible.”

Webb’s Mind-Blowing Capabilities

Using its mid-infrared instruments, Webb captured stunningly detailed images and spectra of light that confirmed the presence of these protoplanetary disks. These disks are encircling stars that are 20 to 30 million years old—practically senior citizens in cosmic terms. According to NASA, earlier assumptions suggested that such disks would dissipate within just a few million years, but the data tells a different story.

In fact, these findings suggest that planets could still be forming in environments with few heavy elements, potentially reshaping how we think planets like Earth—and even entire solar systems—come into being.

Two Theories, One Big Question

So, why are these disks hanging around longer than expected? Astronomers have floated two intriguing possibilities. First, the radiation pressure from the young stars in NGC 346 might not be strong enough to blow away the disks’ gas and dust as quickly as it does in other environments. Alternatively, the gas clouds in this region might be larger, producing bigger and more durable disks.

Guido De Marchi of the European Space Research and Technology Centre puts it best: “This discovery forces us to rethink how planets form, especially in the early universe. We might be looking at a far more common process than we ever imagined.”

A New Perspective on the Universe

The implications are cosmic in scale. These findings suggest that planets may have been forming far more often in the universe’s infancy than previously believed, even in regions poor in heavy elements. If true, it paints a richer, more dynamic picture of the early cosmos.

Webb’s success in confirming these disks not only validates earlier Hubble observations but also highlights how far we’ve come in understanding the vast complexities of space. One thing is clear: the universe still has plenty of surprises in store for us.

This groundbreaking discovery is yet another feather in Webb’s cap and a testament to humanity’s unending curiosity about the cosmos. Keep your eyes to the stars; the best may be yet to come.

Leave a Reply