Quaise, a revolutionary energy firm founded in 2020, has gained a lot of attention for its bold objective of digging deeper into the crust of our planet than anyone has ever gone before. After the completion of the first phase of venture capital investment, the MIT spin-off has now received a maximum of US$63 million, a promising start that might render geothermal energy more attainable to more people across the globe.

The company’s plan to reach deeper to the Earth’s core is to combine traditional drilling technologies with a megawatt-power lamp inspired by the technology that might someday contribute to making nuclear fusion energy a reality.

Geothermal energy

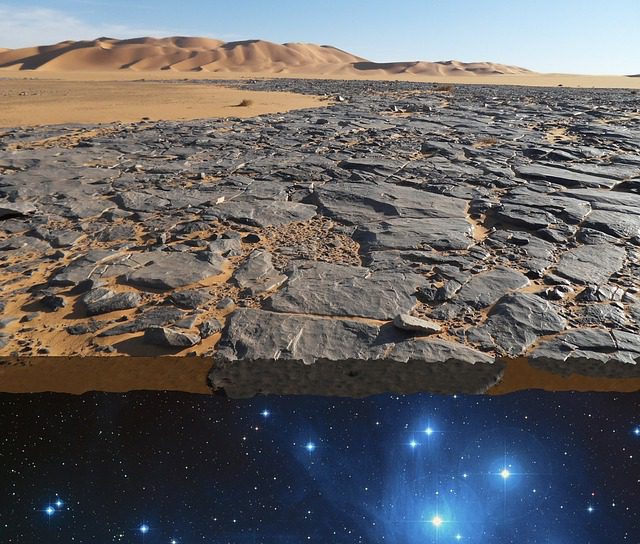

Geothermal energy has been relegated to the background of renewable energy sources. With solar and wind power rapidly dominating the green energy industry, attempts to harness the immense pool of heat under our feet are lagging. It’s not difficult to see why. Despite the fact that geothermal energy is a great source of pure, uninterruptible, endless energy, there are only a few areas where hot rocks appropriate for geothermal energy harvesting are near to the surface.

Quaise wants to alter that by using technology that allows us to burn holes in the crust down to unprecedented levels. To yet, our greatest attempts to gnaw through the earth’s natural skin have stalled at roughly 12.3 kilometers. Whereas the Kola Superdeep Borehole and many like it may have hit their limits, they are nonetheless incredible technical accomplishments.

We’d have to discover a means to grind away at stuff crushed by dozens of km of overhanging rock, then carry it back up to the surface, if we wanted to go any farther. Digging equipment would also have to be able to pulverize rock at temperatures over 180 degrees Celsius. It will also require some imaginative planning to turn the drill bits over such a vast distance.

One possible solution to the aforementioned issues is to dig less and burn more. Quaise’s method, which is based on nuclear fusion research at the MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center, uses millimeter-long pulses of electromagnetic radiation to compel atoms to melt together. By tossing electrons at high speeds under intense magnetic fields, gyrotrons can effectively churn out uninterrupted streams of electromagnetic radiation.

Quaise hopes to be able to blast its way through the hardest, hot rock down to levels of roughly 20 kilometers in a couple of months by linking up a megawatt-power gyrotron to the newest in cut equipment. The temperature of the rock layers may reach over 500 degrees Celsius at these distances, which is hot enough to turn any liquid water pushed down there into a vapor-like supercritical condition, ideal for producing power. Quaise expects to have field-deployable equipment delivering proof-of-concept activities sometime in the following two years, thanks to its seed and venture funds. If all goes according to plan, the system might be operational and generating electricity by 2026.

Leave a Reply