What we thought we knew about volcanoes prior to the recent revelations from the Fagradalsfjall eruptions in Iceland, is now radically different. It’s not often that we acquire knowledge that revolutionizes our worldview. Such an epiphany has just recently come to light, however, for Earth scientist Matthew Jackson of the University of California, Santa Barbara and the hundreds of volcanologists throughout the world.

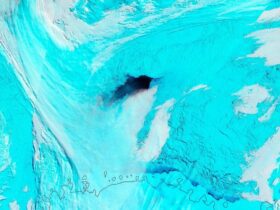

The geologists, led by Saemundur Halldórsson of the University of Iceland, set out to determine where in the mantle the magma had formed, how far below the surface it had been stored before the eruption, and what had been occurring in the reservoir prior to and during the eruption. These may seem like basic inquiries, yet they pose some of the greatest difficulties for volcanologists. This is because many active sites are located in inaccessible, dangerous, and isolated areas, and eruptions may occur at any time.

According to the article, during the first several weeks, the depleted magma type that had been building up in the reservoir around 10 miles (16 km) below the surface was what was erupting. In April, however, it became clear that a new form of deeper, richer melt was recharging the chamber. These came from a distinct section of the Icelandic mantle plume’s upwelling zone. This new magma exhibited a larger magnesium level and a higher amount of carbon dioxide gas, indicating a less altered chemical makeup. As a result, it seemed that less gas had been released from the magma at these greater depths. In May, the deeper, richer magma had become the dominant flow. They claim that never previously have these quick, severe variations in magma composition been seen in near real-time at such a hotspot.

This finding represents a “key limitation” for the scientists as they develop models of volcanoes all around the planet. However, it is still unclear how often this phenomena is or what role it plays in setting off an eruption at other volcanoes.

Leave a Reply