Researchers from Ohio State University have come up with a novel way to detect dark matter, one of the greatest mysteries to the cosmological community. Using ground-based radar to search for ionization trails, similar to those produced by meteors streaking through the atmosphere, researchers are hoping to use the Earth’s atmosphere as a massive particle detector. If successful, these results would help narrow down the range of possible characteristics of dark matter particles.

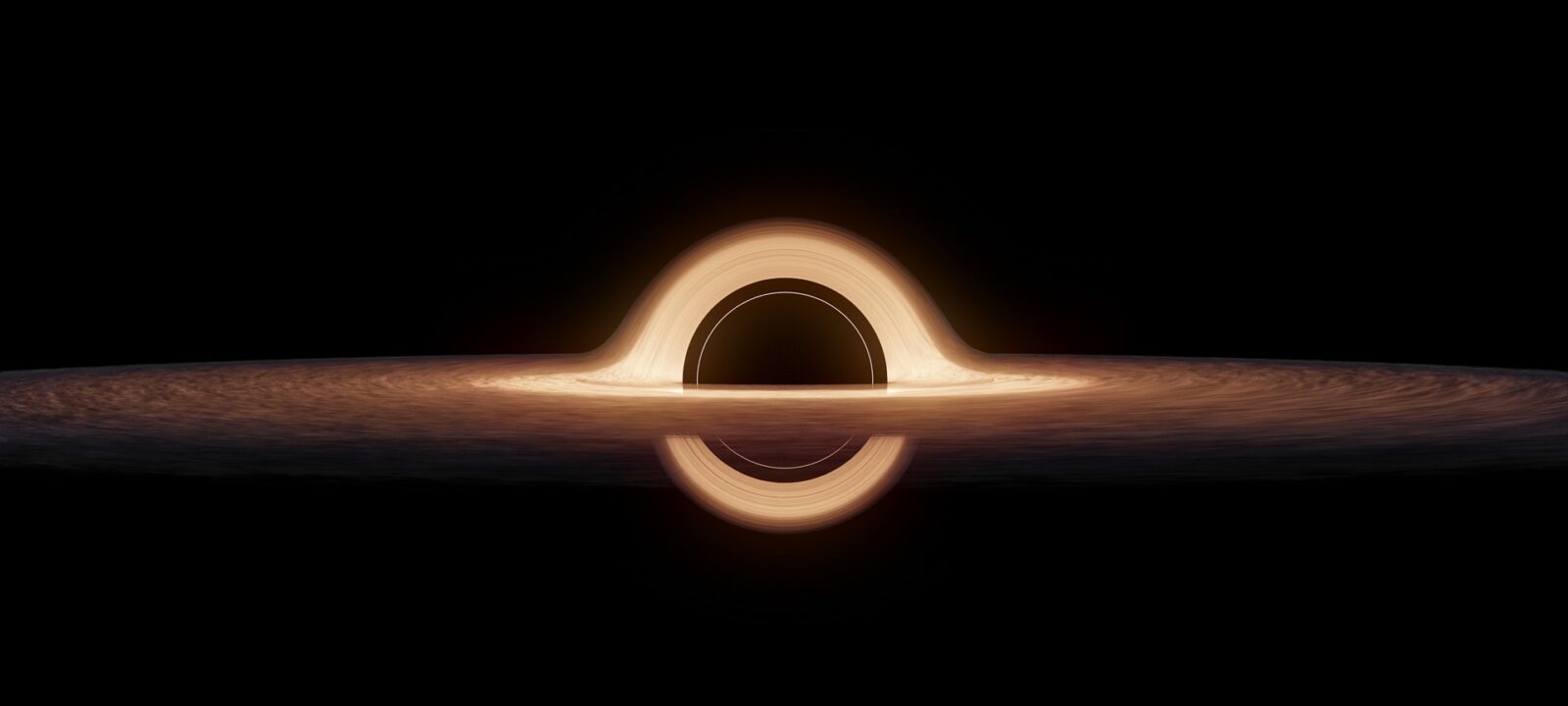

The existence of dark matter has been accepted by most physicists since Lord Kelvin calculated that the mass of stars in the Milky Way was much less than total mass of the galaxy. However, current technology can still only detect so much of the matter in the universe, leaving 85% unaccounted for. It is believed dark matter is made of some type of as-yet-undiscovered particle and is typically only detected through its gravitational influence.

John Beacom of Ohio State University has come up with an experiment to detect the characteristics of this particle, by adapting meteor-detecting radar technology. When a meteoroid enters the atmosphere, it compresses the air in front of it as it moves faster than air can move out of the way, creating and ionizing atmosphere. This forms a trail that can be detected by the radar and is not visible in visible-light telescopes.

If dark matter exists within the range of possibilities calculated by theoretical physicists, these particles should interact with “normal” matter more easily, though still quite rarely. Beacom’s hypothesis is that if particles are large, they may be too heavy to be detected on the ground, but should still produce an ionization trail in the atmosphere, like a meteor.

This experiment is only meant to answer one question: If dark matter particles large, heavy, and rare, or are they small, light, and numerous? All other evidence for dark matter comes from observations made by the earliest astronomers in the 1800s, through to the present day. Early radio astronomers in the 1960s noticed that spiral galaxies spun too fast around the edges, while observations in the 1980s detected gravitational lensing and CMBR anisotropies, all suggesting the existence of dark matter.

Not only would the results of this experiment help us to better understand dark matter, but the technique itself could lead to further breakthroughs in uncovering this long-elusive element of the universe. This article was originally published by Allen Versfeld of Universe Today, but you can check it out right here.

Leave a Reply